Adnan Softic

Tight tissue - or - The body is my temple

| Artist | Adnan Softic |

| Year | 1999 |

| Duration | 5:41 min |

| Technical info | Film Super 8 |

| Contact | |

About the video

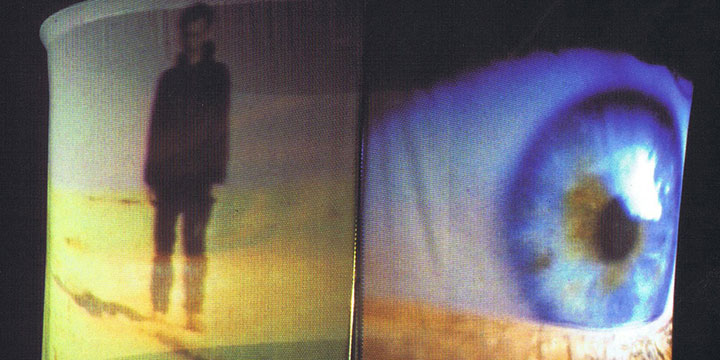

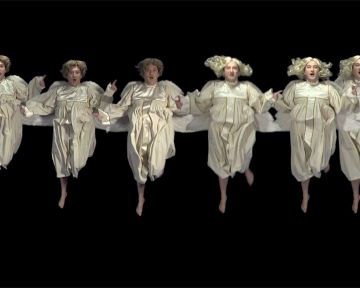

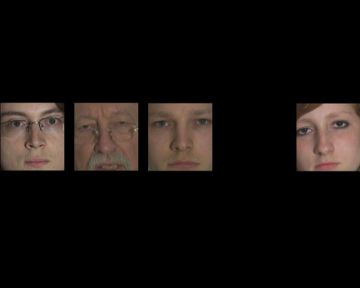

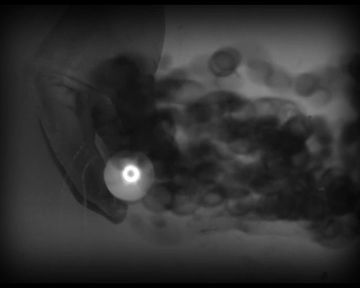

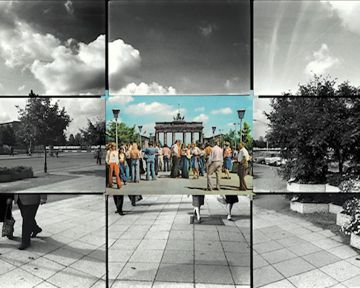

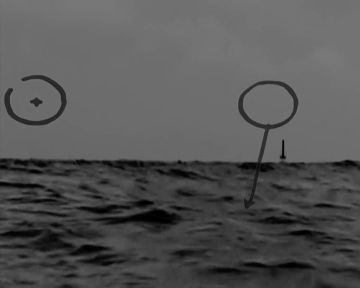

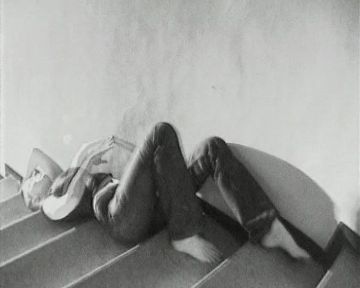

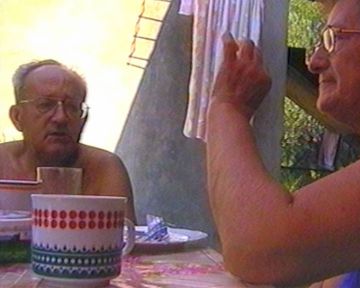

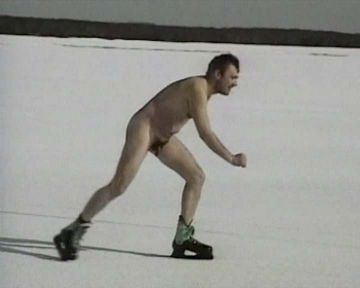

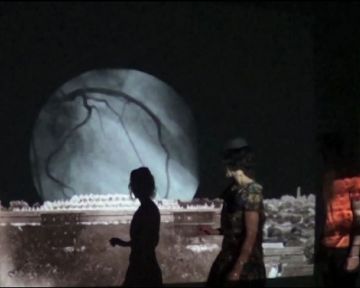

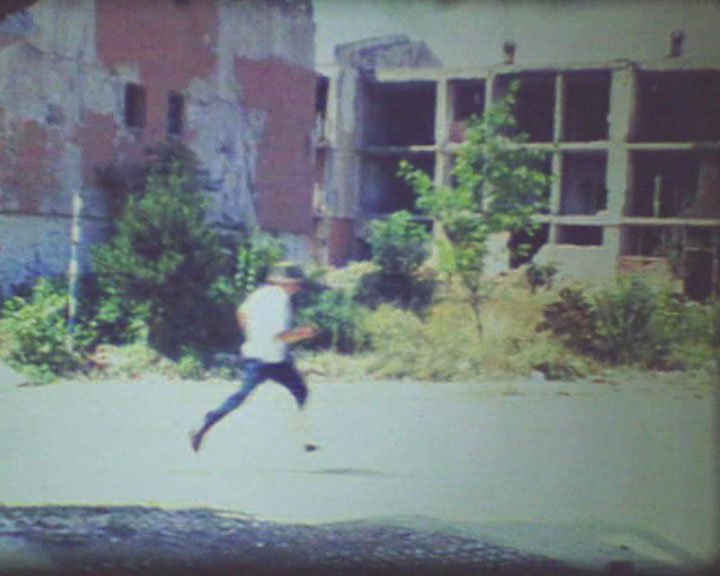

Four young men are exerting sports in completely destroyed areas of Sarajevo. From off-stage one hears a number of opinions about body aesthetics.

Nothing without disturbance

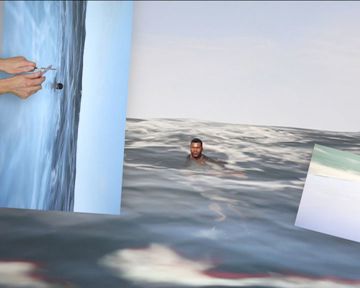

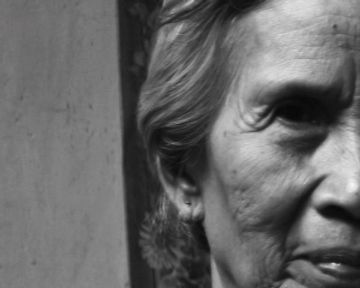

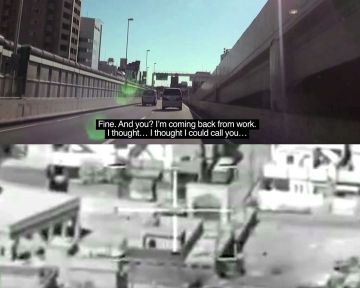

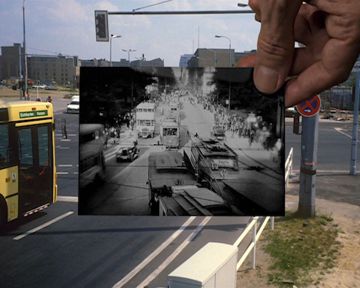

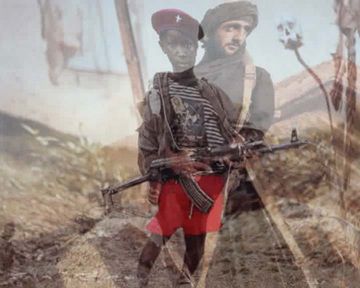

Four boys travel to Sarajevo. For Adnan and Jons a homecoming following years of devastation, of pain. Returning, back home. All of them want to make a film, record the big moment, play at being a director. They argue for all they are worth. Dispute as a starting point, as a form, as an approach. No taking it easy, no pity for one’s own fate. We owe it to the dead, to history, to the right one, our history.

The film shows none of this, or perhaps all of it: The consequences of the situation, the hopelessness. We run around, lose the overview, the orientation, devastate the devastated and rise up.

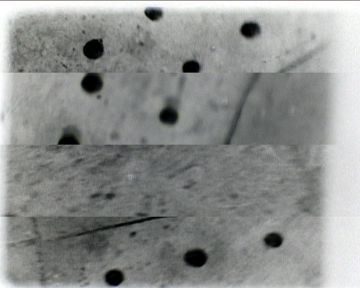

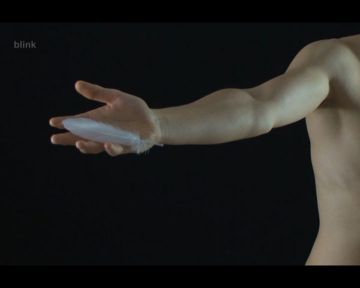

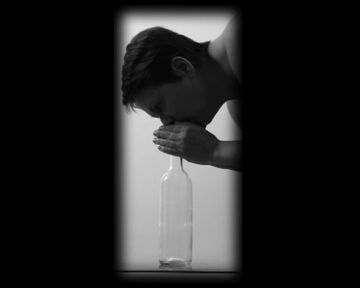

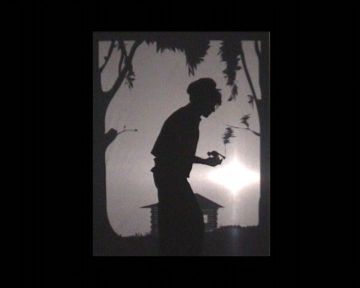

Our gaze is directed at the body in order to show what should not be shown: That which is present everywhere, that one cannot imagine not being there, the consequences of the war, the besiegement, the ruins of Sarajevo. Inside: Firm tissue or my body is my temple.

What a title, what grandeur…One must be daring, and the film dares to do very much.

It puts an end to the dispute, over, finished.

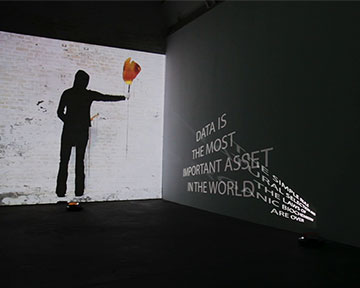

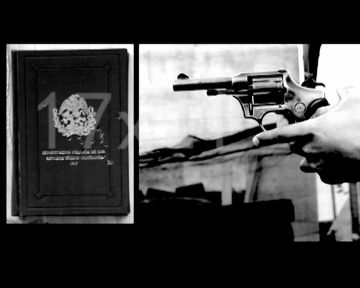

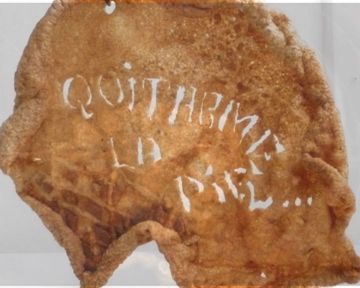

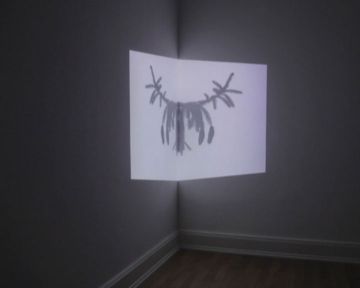

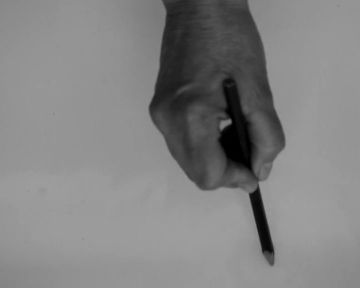

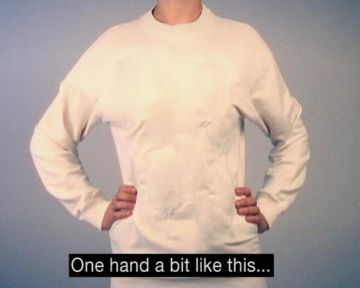

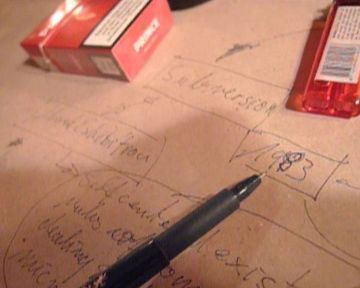

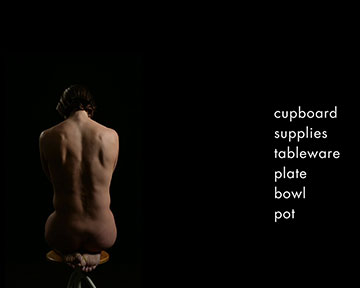

There is no more arguing, statements are made, as a voice-over. The text is pure assertion. It strings together fragments of thought above the body and its function of creating identity. Like a manifest, much too serious to be taken seriously.

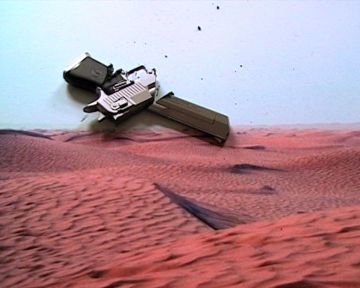

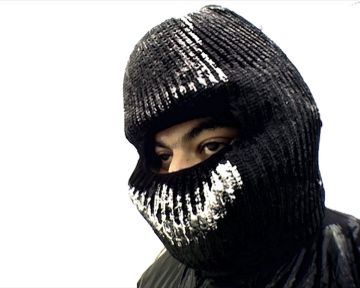

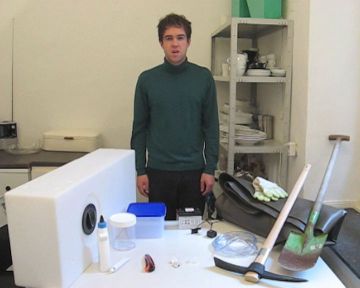

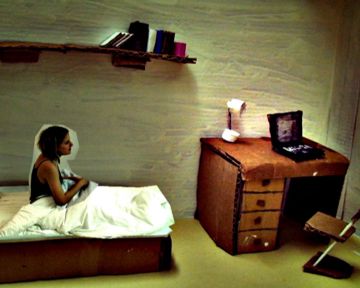

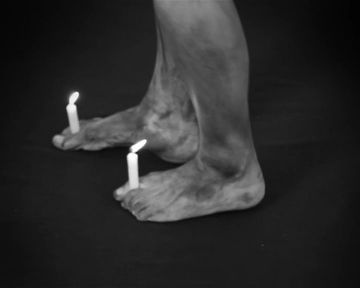

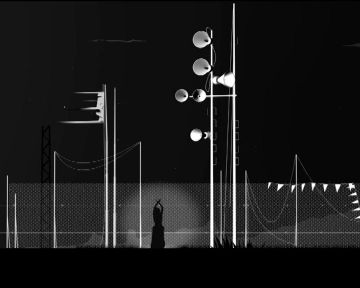

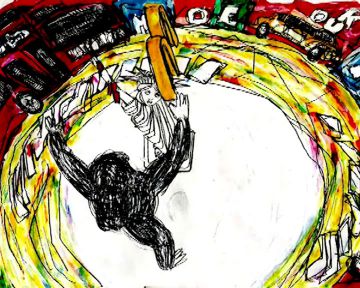

The images on the other hand speak for themselves, they are absurd enough. Four boys who prepare themselves in the ruins of Sarajevo, do sport, hold their competitions. Their own Olympics, the oldest kind of spectacle: Olympics, competition, conflict, war. One can derive even more from it, the references are there, yet the film does not do this.

Nothing is projected outwards but instead it is crammed into the emptiness. No aesthetic of destruction, of emptiness, no putting something on show but an appropriation of destruction. Our own playground. We are cheerful and healthy, walk, run, start to throw things and get the machinery going. A paradise for city kids – without innocence.

Once again a reference to the big kids’ game? The joy of destruction?

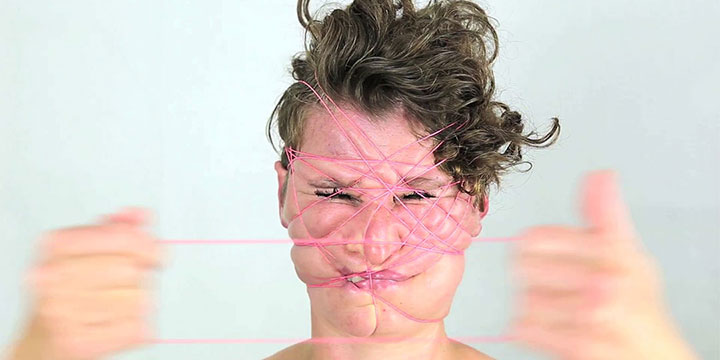

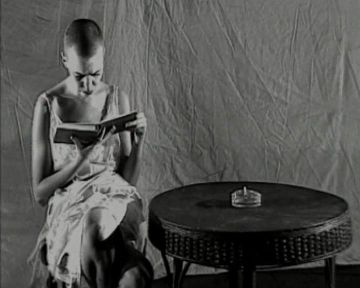

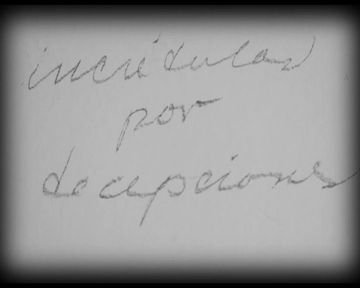

Yes and no. One can interpret it like this however the film does not succumb to the seductive nature of the images but instead speaks against it with an image of the body. “Hands must be beautiful, teeth are important, collarbone and hip bone, sensual mouths, beautiful thighs, eyes and eyelashes, the man’s back is strong, broad, V-shaped…”. A categorical body image. Also a socialist, fascist exemplary image?

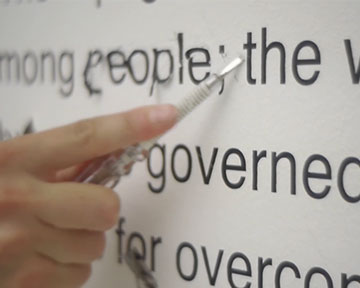

It is precisely here, at the seemingly weakest point, that the film shows its true strength. It is the performative act of reading that counteracts and at the same time compensates the image of the absolute, the unquestionable. As a result the film allows itself to say what it says and to show what it shows.

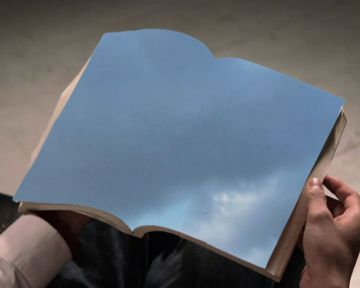

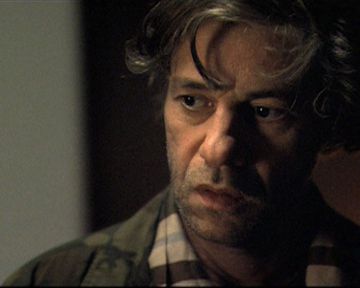

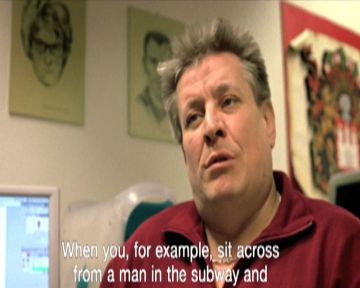

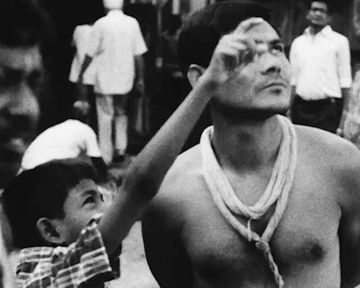

It is the author himself who while turning the pages as if searching for what he wants to say, at the same time questions the sincerity of his statement. More or less denies it. It is both magnificent and disturbing how he stumbles over his words, his voice remaining sober and dry, disregarding his own blunders, quite naturally, almost provocatively.

Yes to mistakes! Yes to blunders! Own up to them, recognize them and generate them. This approach breaks free of the inviolability of the manifest and brings it back down to the level of something sensitive, experienceable.

The layer of the image and the sound are superimposed upon one another and meet without touching. As a result, an intermediate space is created, a third reality that denies the viewer the possibility of an unambiguous interpretation.

The film ends like this: "… always the exterior and even worse, everything at first sight. It is so senseless, one only thinks about the body." How could such an assertion hold its ground if it were not the result of a form of denial that reveals its rather crude affirmative strength in precisely this disturbance, this punk attitude.

Luis Gal Iglesias

Credits

Idea, realisation: Adnan Softić

Contributors: Frank Henne, Luis Gal, Adnan Softić, Jons Vukorep

© kinolom - Adnan Softić

Adnan Softic - Tight tissue - or - The body is my temple

Four young men are exerting sports in completely destroyed areas of Sarajevo. From off-stage one hears a number of opinions about body aesthetics. Nothing without disturbance Four boys travel to Sarajevo. For Adnan and Jons a homecoming following years of devastation, of pain. Returning, back home. All of them want to make a film, record the big moment, play at being a director. They argue for all they are worth. Dispute as a starting point, as a form, as an approach. No taking it easy, no pity for one’s own fate. We owe it to the dead, to history, to the right one, our history. The film shows none of this, or perhaps all of it: The consequences of the situation, the hopelessness. We run around, lose the overview, the orientation, devastate the devastated and rise up. Our gaze is directed at the body in order to show what should not be shown: That which is present everywhere, that one cannot imagine not being there, the consequences of the war, the besiegement, the ruins of Sarajevo. Inside: Firm tissue or my body is my temple. What a title, what grandeur…One must be daring, and the film dares to do very much. It puts an end to the dispute, over, finished. There is no more arguing, statements are made, as a voice-over. The text is pure assertion. It strings together fragments of thought above the body and its function of creating identity. Like a manifest, much too serious to be taken seriously. The images on the other hand speak for themselves, they are absurd enough. Four boys who prepare themselves in the ruins of Sarajevo, do sport, hold their competitions. Their own Olympics, the oldest kind of spectacle: Olympics, competition, conflict, war. One can derive even more from it, the references are there, yet the film does not do this. Nothing is projected outwards but instead it is crammed into the emptiness. No aesthetic of destruction, of emptiness, no putting something on show but an appropriation of destruction. Our own playground. We are cheerful and healthy, walk, run, start to throw things and get the machinery going. A paradise for city kids – without innocence. Once again a reference to the big kids’ game? The joy of destruction? Yes and no. One can interpret it like this however the film does not succumb to the seductive nature of the images but instead speaks against it with an image of the body. “Hands must be beautiful, teeth are important, collarbone and hip bone, sensual mouths, beautiful thighs, eyes and eyelashes, the man’s back is strong, broad, V-shaped…”. A categorical body image. Also a socialist, fascist exemplary image? It is precisely here, at the seemingly weakest point, that the film shows its true strength. It is the performative act of reading that counteracts and at the same time compensates the image of the absolute, the unquestionable. As a result the film allows itself to say what it says and to show what it shows. It is the author himself who while turning the pages as if searching for what he wants to say, at the same time questions the sincerity of his statement. More or less denies it. It is both magnificent and disturbing how he stumbles over his words, his voice remaining sober and dry, disregarding his own blunders, quite naturally, almost provocatively. Yes to mistakes! Yes to blunders! Own up to them, recognize them and generate them. This approach breaks free of the inviolability of the manifest and brings it back down to the level of something sensitive, experienceable. The layer of the image and the sound are superimposed upon one another and meet without touching. As a result, an intermediate space is created, a third reality that denies the viewer the possibility of an unambiguous interpretation. The film ends like this: … always the exterior and even worse, everything at first sight. It is so senseless, one only thinks about the body. How could such an assertion hold its ground if it were not the result of a form of denial that reveals its rather crude affirmative strength in precisely this disturbance, this punk attitude. Luis Gal Iglesias