Galerie Jocelyn Wolff

78, rue Julien-Lacroix

F-75020 Paris

T + 33 (0)1 42 03 05 65

www.galeriewolff.com

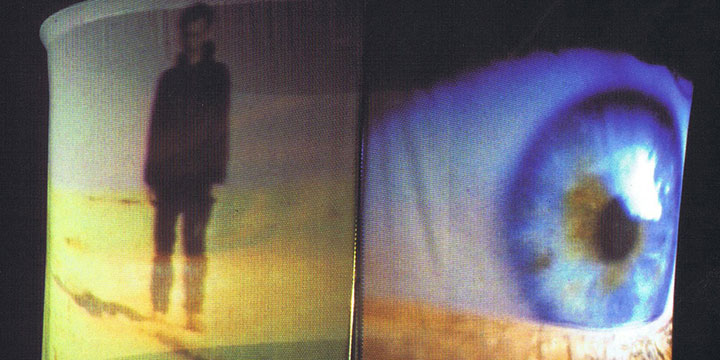

Scratched images as though it was pouring down rain. The film seems wrinkled by contagion with the face of the spinners, captives of the Manákis brothers, those cameramen who ran from one end of the Balkans to the other at the dawn of the 20th century to film minuscule gestures and lives. Tentacular, they spin the wool into balls of yarn. I grope about blindly over the parchment face of a woman from a time past, in a small Greek village in 1905. The uneven depth of these images brings me to a full stop: these are the first minutes of the film by Théo Angelopoulos, Ulysses’ Gaze (1995). We can hear the humming of the projector, the film unreeling and the scratching of the images. The spinners, these are the Parcae, the sisters Nona, Decima and Morta who determine the fate of men, emerging between their agile fingers.

Spinning out along a trace, filming the traces. What indications do these images give? The index, this is the pointed finger that indicates and identifies. It is said that images give access, allows us to attach to and enter into contact with something in the real. That, there, here. It is even said that the print is irrefutable, that it instils the real in the image, like an impregnated cloth. A trace that spreads, that blots, indelible. If these images are clues, if they are traces of something – a place, an event, a presence, a face, an instant –, they impose a investigative-like method. A way of doing things that is much like an object caught up in the spinning. A film in which sewing is presented, not so much as an unstitched film, as one in which the threads are being pulled, one by one, so to undo the knots, unfold what is involved and see if it leads somewhere.

It is about a visual methodology that involves darning the place where it is torn, there where it overlaps, or where some part is missing. Each film in this program invests the grade-related potential of cinema or, to speak like Carlo Ginzburg, make possible a model of knowledge using stories in which the clues and the traces brush over the surface of the images. A writing of the story, through the visual, that restores the individuality, the event while leading on with the investigation. The trace, it is both the piece of evidence of what once was and the presage of what is to come; filming traces, it is to conjugate to the past – always in past tense –, to the present and the future.

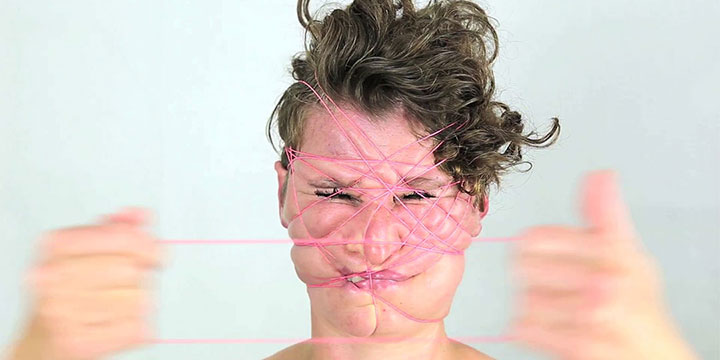

Let’s make a detour. Here, it is not about following up a clue, like the historian who takes on the role as both the detective and novelist, to write the fictitious true-false histories. The gesture of cutting, as terms of separation, is not far from that involved in sewing, which forms a scar: the film proceeds from the hesitation between separation and reconciliation, it is the art of framing that separates as much as it is the editing that stitches; a violent and Balkan art that becomes solves itself through the editing procedure. In spite of what Ginzburg would think, I swap the investigation for the knitwear.

The weaving of these contradictory, jerky temporalities evokes a seismic tremor that produces the autopsy of the images. With the magnifying glass, that which increases the visual acuity tenfold and allows us to see better, the images end up blurred. Where we were seeing contact, adherence, in short, coherence between the parts, there is suddenly a distance, like a standard deviation that authorizes doubt, suspicion. We become near-sighted. The circumflex eye brow succeeds the pointed index, the examination of the images takes place afterwards. Eureka, worried.

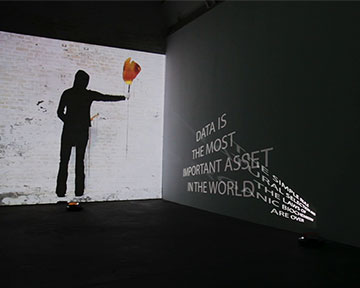

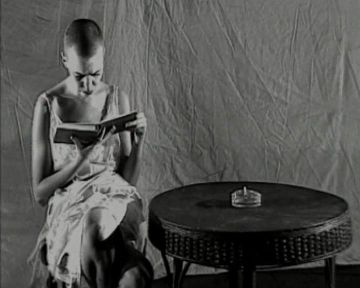

We know now of what importance these women were since the beginning of cinema, these “petites mains” or “unqualified workers” who colored the film by hand for Pathé or workshops in the rue de Bac, at the home of Mrs. Elizabeth Thuillier. These “petites mains” that the Hollywood industry reserved for editing – manual and precise technical work – but were not mentioned in the credits. In 1926, the Los Angeles Times ran as a headline that one of the most important positions in the cinema industry belonged to women: cutters or editors, the vagueness of the term used at the time tells much about the amplitude of the editing gesture. Edit refers both to cutting-pasting-assembling and to the editorial scope of this series of gestures. Weaving as editing and tools for patching replaces the spinning logic of the investigation. It is not so much to Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) in The Maltese Falcon by John Huston that this program gives tribute as much as to Margaret Booth, Irene Morra, Blanche Sewell and other Rose Smiths. The “cutter” that mends the films and whose ancestors include the Manákis brothers’ spinners. The thread and the traces with all of their knots, stitching, hem stitches and overcast stitches that weave the account of an alternative and reticular history.

The films in this program conduct an investigation along the thread of the true and the false, from the personal to collective stories, from a space that is both real and fictitious; however the intrigue does not involve so much the resolution as it does the cut-and-stitch method and its issues. This point of reprise, this mending of the void left between the images, is also a reprise or reshowing of the images: a double gesture of stitching and re-use. This reprise engages a detailed examination of an old-fashioned, deterministic, linear, historical model, the one with a one-way history. Cutting, stitching and scarring. In the mesh of the network, parallel stories, unpublished faces, an imaginary geography are easily read. The reprise suggests a protocol for examining the images using their very materiality. It is the entire thread, the film that is secreted by the spinning spider, and, as Ovid (1971/299) describes, “... the rest was belly. Still from this she ever spins a thread; and now, as a spider, she exercises her old-time weaver-art.”

Eline Grignard