SEEMINGLY INNOCUOUS VIOLENCE

If it were not for the date of 1978 that completes the title of the video Cidade Submersa [Submerged City] (2010), its relation to the daily reality of several towns in Brazil would be immediately clear. Immediately clear because the title is associated with the terrible tragedies that can kill and make thousands of families homeless in the rainy season. Seen from this perspective, 1978 – Cidade Submersa tackles an imminent social, geographical, political, educational, economical and cultural problem that af- fects hundreds of thousands of people. Caetano Dias foresaw the memorial relationship between the citizens and the city. Just imagine a permanently flooded city. What else could it be other than a fount of memories and losses? Like images projected in the future Caetano’s video poetically articulates futures of some- thing that increasingly we contemplate passively, because to control nature is irrevocable.

However, as in the work Cristo de Rapadura [Sugar Christ] in which the artist uses the history of Bahia in order to subvert it, reconfigure it and transform it into mythical language – in the Barthesian sense of the term –, in 1978 – Cidade Submersa, both the date and the title of the video are related to Remanso, a small town in the state of Bahia. Here is the idea according to which the text-image association is only superficially anodyne. The town is not going to be submerged; it has been so for a long time, ever since the construction of a dam. In the video and in the series of photographs entitled A´gua Invertida (2010) one can also see a water tank, the only object visible above the waters. Stripped of any usefulness, its reproduction in the world of the arts reminds one ironically of something ready-made, as instead of containing water, this monumental construction has ended up measuring the water-level over the city.

In this way Caetano Dias explores the world of documentary film, and at the same time creates narratives at the margins of reality and fiction in this way filming a local fisherman sailing over his own town. Apart from individual memories, he contrib- utes to building a postmemory for those who have only known New Remanso, built in the surrounding area after 1978. And so the artist draws together the time and historical facts that mark our contemporaneity, disintegrating the documentary value of the video and above all revealing the violence that while appar- ently innocuous, transforms memories into open wounds and what is to come into a natural reaction to past acts. 1978 and 2010 have never been so close.

UNINTERRUPTED CYCLES

The first and last scenes of the video Fazendo Água (2010) are deliberately similar: in both cases what we see is the image of the sea. Just as it is hard to tell them apart, it is also difficult to identify where the images were taken. But more than anything else it is important to note the way in which Caetano Dias has married the coexistence of parallel times, each associated with different spaces and existences. Thus, on seeing the vertiginous sky above the horizon, the eye of the onlooker is divided and confused by the calm repetitive movements of the ocean water. A beat that is out of synch with the calm rhythm of the waves and the violence of the clouds keeps pace with the swinging arms of a man, who moves slowly onwards until he comes across a small boat, on which he seems to be able to control what is around him.

An extract from a poem by Fernando Pessoa reminds us of hu¬man frailty: «a vida é breve, a alma é vasta» [life is brief, the soul is vast]. The frailty of life to which Pessoa was alluding is manifested here in the act of sinking: although the Brazilian expression “Fazendo Água” [literally “making water”] is used to describe a sinking boat, in his piece Fazendo Água Caetano shows us a man filling his boat with buckets of water that he is in turn filling from the sea. It seems that he is unaware of the imminence of his actions. If indeed life is fleeting, it is so because of the alienation of the self, which while seeming to act is often conduced to put an end its own existence. And so – in uninterrupted cycles – the desires and the control over the tini¬est part of nature that the self would seem to deter dissipate. This video, an important example Caetano Dias’ work, has close ties to the thinking of Seneca, in his turn influenced by Lucilius, on the great problem of watching life pass by as we create the conditions for our own drowning.

Josué Mattos

Salvador - São Paulo, January 2010

Josué Mattos graduated in History of Art and Archeology from the Universi¬té Paris X Nanterre (Paris, France), and has Master’s degrees in the Histo¬ry of Contemporary Art and in Curatorial Practice and Cultural Management from the Université Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne (Paris, France) with a thesis on questions of semiology related to Brazilian Art production. His central in¬terest is the re-appropriation of myth and of the memory of the avant-garde today. Among the projects that he has curated are the exhibitions Terres et Cieux and En faisant des étoiles for the Inter-câmbio Festival.

(1) cf. Marianne hirsch, family frames. Photography narrative and postmemory, cambridge, harvard

University press, 1997.

THE WORLDS OF CAETANO DIAS

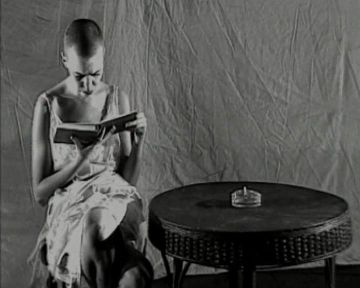

Caetano Dias’ work should always be considered in the con¬text of Salvador, Bahia, where the artist lives. In his video UMA, taken on a beach in Salvador, he filmed a love scene between a black girl and a white man at the water’s edge. Behind this ap¬parently voyeuristic scene is the social and cultural context that Caetano Dias describes for us relating to the difficulty of mis¬cegenation beyond sexual relationships: loss of meaning in the fantasy of a mix that is complicated, perhaps even impossible, whether it is one of bodies or of cultures. Appropriating images is his way of emphasising his view of the world, of beings and of their objects, as they are the captive petrified constituents of this world. The body, place and mark of the performance in this way unveil what Rosalind Krauss in “Le Photographique” calls not “an entity being seen, but rather an entity being perceived”.

Caetano Dias also treats (supposedly) popular culture, his work embraces both artistic and religious syncretism (was not POP ART aesthetic syncretism?) like candomblé (where the Yoruba animism of Benin is melded with Catholicism). The artist thus preserves the enigma of creation whatever its destiny may be: aesthetic, totemic or religious. This is why, in a great number of his works, he mixes sensuality and spirituality, paganism and religion, sweetness and violence, archaism and modernity. Through his sculptures and videos he re-enacts the vulnerability of the body having become a cliché in the world of media, of religion or of tradition. His work is founded on perception, nature and on the combination of the things he sees in human relation¬ships. The figurative body or the body with its ironic flourishes, like these walls built of sugar that he builds in the slums; he inscribes in them a derisory and edible delineation of a space without administrative reality, just like the slums themselves.

Caetano Dias underlines the values of political, historical, social, religious or aesthetic truths in order to contest them. These enti¬ties that he raises demonstrate his commitment to revealing the pathways and boundaries between what is public, private and in¬timate, and the constitution of the individual and the community.

In his video, O Mundo de Janiele [The world of Janiele], a high¬light at the Paço das Artes in São Paulo, which was acquired by the Museu Berardo de Lisboa, and which I had the honour to introduce in 2009, he makes us penetrate this “concrete love jungle” of the slums. He films a girl playing with a hula-hoop; at first sight this scene seems simple and playful with its strange childish music that sounds like it is coming from a music box. Lit-tle by little, through the repetition of the movement and the slow appearance of the girl’s face and then her entire body, reigning

FALTANDO....

“CAETANO DIAS AND HIS RELATIONAL AESTHETICS”

“I drank of life. I upheld the gods. I align myself with death. The windows of the future open on living tradition”

Murilo Mendes

To write about Caetano Dias is a great pleasure yet also a great challenge. It is not just the small routine pleasure of someone telling a story. It is a greater pleasure, one that challenges us to penetrate the mysteries of art, and even the art of mystery. By this I don’t mean that art possesses a mystery – however real. The pleasure that this artist’s work offers us is one that is more conditioning than conditioned, it encompasses a small mystery that leads us to believe that we are the very thing that it shows us. Caetano’s art is something that allows us to say, as if in ju¬bilation: “but this image is us, our sensitivity, our way of being”, this is because more than anything else it is a source of time and subjectivity.

Caetano Dias works with a wide range of media – painting, sculpture, photography, video, installations, urban interventions and many other objects and unspecific actions -, this does with¬out a doubt make the task of analysing his work more difficult. One could probably express this by describing him as a multime¬dia artist. But with the rise of digital art and new image technol¬ogy this term has been overused.

In truth, Caetano is much more than a multimedia artist; he is more even than an artist who makes the medium a determining factor in itself. The medium is the means to achieve the work’s potential, it is not an end in itself, contrary to the approach of many artists today, who adopt, perhaps unconsciously, McLu¬han’s phrase: “the medium is the massage”. Not a supporter of technological self-reference, Caetano prefers to use the medium in function of the issues that he tackles. Caetano doesn’t make videos because he doesn’t know how to paint or sculpt, nor be¬cause he thinks that multimedia is a more evolved medium (in art, paradigm changes don’t necessarily imply evolution), but because video serves him very well as a means of expression. If he lacks a suitable medium Caetano is capable of inventing his own, of coming up with techniques inspired by new conver¬gences.

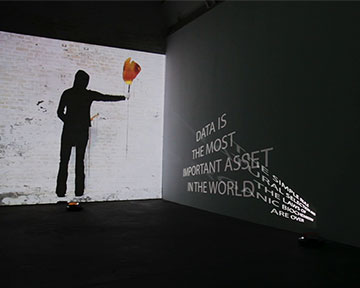

In his series BESTIÁRIO DIGITAL the artist extracts images from pornographic sites, and then blurs them, emptying them of direct references to the object shown in its pornographic nudity The ghostly bodies take on a pictorial quality, like an invitation into a dream world. The bodies are suddenly almost abstract; they make us imagine things, which could in a way make us think that Caetano’s strategy consists of destroying the cliché so as to give us an eroticized image, subverting the logic of the pornographic images. As we know, in this so-called era of “Civi¬lization of the image”, much of the time images are clichés, in which pornography and violence are the dominant tendencies.

In another of his works, which has more than one version (RE¬SPIRE, an interactive installation and PASSEIO NEOCONCRETO [Neoconcrete tour], a video-sculpture), the artist shows us a man crouching in a foetal position, in the water, inside a tank: is he sleeping? Dreaming? Breathing normally or suffocating? In the interactive version it is up to the onlooker, who with the click of a mouse, can save the character from drowning or not. Obviously this drowning is symbolic, in the sense that the situ¬ation holds within it an entire imagery spanning the foetus and birth to dreams and death. In the more recent video-sculpture, the image of the man in the water is projected on a piece of the sidewalk above which we can see a small hole. This piece of sidewalk is a real object, as if Caetano had appropriated a piece of the actual sidewalk. Suddenly, this image takes on new dimensions, making us think of the homeless people living on the sidewalks of Brazilian cities.

In order to understand the potency of this image, and how it affects our cultural relationships, we can evoke the problem of the clichéd image. Every society has its misery and beauty. But for people to support each other and their surrounding world, it is necessary to make what is intolerable disappear, our interior must be like our exterior: these are our sensory-motor schemes. We all routinely suffer a process of subjection that makes us insensitive to what is intolerable, both in its misery and in its beauty (the sublime). The big question is: what happens when our sensory-motor schemes crumble and fall apart? Is there anyone who has not on occasion felt overwhelmed by a strong sensation of strangeness when faced with the most banal and familiar of things?

In her exquisite short story, “A Bela e A Fera ou Uma Ferida Grande Demais” [Beauty and the Beast, or a Wound Too Great], Clarice Lispector shows us, through the meeting of an upper-class woman and a beggar living on the streets of Copacabana, what happens when these sensory-motor schemes fall apart. The beggar asks the woman for some change and in doing so shows an enormous wound on his leg. Suddenly it is as if all the misery of the world had exploded from within that wound, and it becomes too big. From this point on, a sense of strangeness is created between the two characters. It is as if they no longer know who they are, how to speak, how to act, etc. They become paralysed and this paralysation makes their thought blossom, as if they had never really thought before, but only acted mechani¬cally. From this meeting onwards they are never the same again and neither is reality.

The challenge for someone who produces art is in knowing in what way it is possible to extract images (“jamais vu”, purely external) from the clichés (“déjà vu”, purely internal), images that make us see things as if we were seeing them for the first time. This, it seems to me, is the technique Caetano Dias uses in his work. All the other issues contained in his work – the use of distinct mediums, the question of interactivity, the social and cultural themes, issues on the body and the eroticization of life, among other things – come from this central tenet of the opposi¬tion between the image and the cliché.

When nowadays people talk about the importance of the body in contemporary art, we frequently forget that bodies are pure sub¬jectivity or sensitivity. My body is not merely a natural, biological fact, but it extends as far as my habits and my world view extend.

Here it is important to introduce an historical fact. In Brazil, as a result of the neo-concrete rupture, the modern form and its rationalist schemes start to go into decline. This decline was in¬creased with the later works of Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Clark and Lígia Pape, who, from the 1960s turned their works into a super-sensorial process of experimentation for a new way of living. As Mário Pedrosa said in his text “Arte Ambiental, Arte Pós-Moder-na: Hélio Oiticica”, we entered a new cycle, one that was no lon¬ger purely aesthetic, but also cultural, behavioural and ethical.

The issue of the body in this new cycle of contemporary art, in which the Brazilian artists mentioned above no longer worked in the style of the North American or European artists, is linked to a critical concept or attitude: the body is something to be dived into to connect the image and the thought to what is outside it. The work is an inflection, a fold, but the fold experiences the at¬titudes of the body, through the “dive into the body” to use Hélio Oiticica’s expression, which expresses so well the process of aesthetic reversal, the cure for the formalist/modernist obses¬sion. It in is this context of draining the formal repertoire in Brazil in the 1960s that a group of artists were inspired to use per¬formance, installation, cinema, video, and use the body of the artist as the principal player in the work, these included Antônio Manuel, Barrio, Cildo Meireles, Tunga, Anna Bella Geiger, Amé¬lia Toledo, Sônia Andrade, Ana Maria Maiolino, Ivens Machado, Regina Silveira, José Rezende, among others. In the work of these artists, every strategy, every medium, every effort consists in forcing the mind to think about the intolerable parts of the so¬ciety in which we live.

The videos by the group of video-art pioneers in Brazil (Anna Bella Geiger, Sonia Andrade, Ivens Machado, Fernando Coc¬chiarale, Paulo Herkenhoff, Letícia Parente, to name a few), are generally made in a single take, and have commonplace gestures repeated in a ritualistic way – going up and coming down stairs, signing one’s name, putting on make-up, decorat¬ing oneself, eating, playing on a telephone, these things are set up in such a way as to produce an image of the body. In the videos by the group, the image is an inflection, a fold, but the fold experiences the attitudes of the body, the “dive into the body”. In Passagens (1974) Anna Bella Geiger goes slowly up and down the stairs in a constant rhythm, as if in a rite of passage; in Dissolução (1974), Ivens Machado signs his name a hundred times before fading away; in A procura do recorte (1975) (algo aqui esta faltando eu acho....); in Estômago embrulhado, Paulo Herkenhoff transforms the visceral art of eating a newspaper into the pedagogical irony of how “to digest information”; in one of her videos (untitled), Sonia Andrade goes into a trance as a way of showing how intolerable the television that is interrupting her meal is; in Marca registrada (1975), Leticia Parente, embroiders with a needle and thread the words Made in Brazil on the sole of her foot, demonstrating the process of the objectification of the individual in consumer society. In all these videos the body is no longer a Cartesian dichotomy that separates thought from itself, but is rather something to be dived into, to connect thought with that which is external to it, like the unthinkable.

In O MUNDO DE JANIELE (2007), the artist Caetano Dias shows a girl playing with a hula-hoop. The video starts by show¬ing a teenage girl slowly gyrating against the backdrop of a blue sky. We don’t realise what is making the girl’s body move until we are able to see that she is playing with a hula-hoop. The gyration of the hoop is amplified by the gyration of the camera, which makes the world seem to spin around the girl. At the start, it is a low-angle shot, which little by little reveals more of Jan¬iele’s world: a slum in the outskirts of the city of Bahia (as it used to be called when referring to Salvador). The music is the sound of a musical box, which creates a contrast between the child’s dream and the harsh reality of the world to which she belongs. Very little recent work has been so touching, transmitted through the subtlety with which misery and beauty are melded into a real¬ity that is our own; it is as if we were seeing it for the first time. In O mundo de Janiele, just as in the videos by the pioneers, the beauty of the banal familiar movement of the hula-hoop dance is transformed little by little into the intolerableness of the harsh reality that is the world of Brazilian slums.

This process, through which the stripped-down clichés are transformed into fleshed-out images that translate themselves through an effect of strangeness and even renovation and open¬ing up of cultural relationships in general is one of the major tendencies in Caetano’s work. In one of his most polemic recent works, UMA, Caetano shows us a beach on the outskirts of Sal¬vador. Suddenly he notices that there is something completely unexpected going on in that public space. A casual sexual en-counter between a white man and a black woman starts to take place. We feel like we are watching a film. And at first we sense that the image might shock us though we actually perceive the sexual act and all its movements with great naturalness, but also with great erotic intensity.

The question of interactivity is a major one in Caetano’s work. But one should pay attention. In Caetano’s work there are two types of interactivity that interpenetrate each other. On one hand there is social interactivity, formed by relational space-time, inter-human experiences that attempt to free themselves from the normalized ideological restrictions of social relations (and of what is expected from them). In this sense, what Caetano produces as an image and as an intervention is produced as a catalyst that contributes to the emergence of alternative socia¬bility, readjusted times and places for socializing, new ways of collective organization.

On the other hand, there is the interactivity of audience par¬ticipation. In his sculptures and interventions made of sugar (PEQUENO LABIRINTO – CANTO DOCE - (2004), CRISTO DE RAPADURA (2004), BRINQUEDOS (2005), CABEÇAS (2007) – audience participation is essential. PEQUENO LABIRINTO – CANTO DOCE was first created as an installation at the Bienal de Barro de Maracaibo, in 2004. In the corner of the gallery, Caetano created an edible sculpture of sugar. Since then, the artist has created a group of edible sugar sculptures in the form of walls (CANTO DOCE – the second version, erected on a side¬walk in Salvador), labyrinths (CANTO DOCE – third version, in¬stalled in the Calçada train station in Salvador), a body (CRISTO DE RAPADURA) and heads (CABEÇAS). In truth, it is in the relationship with the onlooker that the work is constituted and is completed as a new space for meeting and contact. In some esoteric traditions of reading sacred scriptures, sages defend the idea that the Bible was created for each one of its read¬ers. This makes one think of Caetano’s work. Eating the body of Christ could be part of a collective participatory process in an art work, just as it could be a renewed gesture of communion. As Nicolas Bourriaud has said, contemporary art produces a social interstice in which these experiences and new “possibilities for life” are possible: it seems more urgent to invent potential re¬lationships of communion with the neighbours of today than to intone chants for tomorrow.

One should not forget that Salvador was the capital of Brazil throughout the sugar boom. As such, sugar is part of the history of the “City of Bahia”. However, when commenting on CANTO DOCE (third version), Caetano Dias made it clear that it was not referring to a mythical past, but was proposing new rela¬tionships between people in the present: “the role of culture in the re-enactment of our lives is like a creative process where we change the conditions that create oppression and monotony. Re-enchantment does not entail a return to a mythical past, it means touching the mystery of the world, turning routine and repetition into happiness, playfulness. This urban intervention, the wall of sugar, changes the flow and paths of the pedestrians in a different way from the walls that normally segregate and separate realities. It proposes a change of attitude. It proposes that the flow takes a different path.” And in this way Caetano reconfigures the flow of pedestrians in the Calçada train station.

Caetano’s primary strategy in his art is to invest in the fertile field of social experimentation, as a space of relations that resists the mass culture and uniformity on every side. It is not an art that takes society as its theme, as is often the case in the cultural field, but it turns society into an open force field, one to be ex¬plored, questioned, renewed and eroticized.

The truth is that Caetano’s work offers us a new body, new so¬cial and cultural relationships by offering us images that trans¬form the general conditions for the production of subjectivity. Caetano’s work increasingly concentrates on the relations that his work will create with the public and on the intervention of new forms of social relations. His production determines not just one practical field, but new formal dominions. As well as the in¬trinsically relational character of the art work (its transitivity), the reference figures in the sphere of social relations involving indi¬vidual and/or collective commonplace gestures – eating, sing¬ing, story-telling, playing, courting, working – have now become integral artistic “forms”: and so the different types of collabora¬tion between people, the different forms of social manifestation (games, jokes, parties, sex, movement of passersby), and the meeting places(the beach, the slum, the sidewalk) are Caeta¬no’s raw material for his work with which he creates an opening in the world, to subvert its order. In ZILOMAG, a group of people play with a wooden sculpture, a cube-house, making it roll down the hill in a slum. The cube rolls, the people laugh, and then it is taken back to the top of the hill from where it is pushed back down again. It is in this game, permanently repeated, like the myth of Sisyphus, that the ways of inventing new relationships and collective events have now become the most interesting forms of aesthetic interactivity. It is through the renovation of the social body that art becomes art.

And when today I hear one of the great artists of Bahia sing “é doce morrer no mar” [it’s sweet to die in the sea], I cannot but help think of this other Caetano, who with the mastery of that other, knows how to transform the salt of life into a sweet song.

André Parente

André Parente is an audiovisual artist and researcher in new image tech-nology. In 1987 he completed his doctorate in Paris under the supervision of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze. Since 1987 he has been professor at the Escola de Comunicação at UFRJ, where he founded and still coordinates the Núcleo de Tecnologia da Imagem [Image technology research centre] (N-imagem). He has written several books, including: Imagem-máquina (1993); Sobre o cinema do simulacro (1998); O virtual e o hipertextual (1999); Narrativa e modernidade (2000); Redes sensoriais (2003, with Kátia Maciel); Tramas da rede (2004); Cinema et narrativité (2005) and Preparações e Tarefas (2008). Between 1977 and 2009 he made countless experimental photographs, films, videos and installations, and has shown his work in Brazil and abroad (France, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Mexico, Columbia and Argentina, among other countries).

__________________________________________________

Cf. Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames. Photography Narrative and Post-memory, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1997.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, Le petit prince, 1943, chapter XIV.

Significantly, the video that records the action described in the in first para-graph is called Mar de dentro [The Sea inside](2005).

Lewis Carrol, Alice through the looking glass, 1872.

For further discussion on 20th century sculpture see, Rosalind Krauss, Passages in modern sculpture, 1977.

An explicit reference bt the artist to the works in this series.

In another version, still not made, the house is balanced on a pile of books, which are also eaten by the termites.

See Nicolas Bourriaud, Esthétique relacionelle, 1998.

See for example the series of photographs Pequenas memórias (2006), in which folded paper form geometrical shapes and take on the role of small sketches, intimate designs of imaginary architecture which is yet again al-most oneiric.

Obstrucción de una vía con un contenedor de carga, 1998.

Verde Oliva, 2003.

Safely maneuvering across Lin He Road, 1995.

JACOPO CRIVELLI VISCONTI

The gazes of the residents, standing in the doorways and win¬dows of their houses to watch the unusual scene, are transfixed, amused and slightly bewildered; a toothless old lady is laughing. The men push the sculpture up the hill, between the simple hous¬es of rough bricks and mortar with their concrete pillars visible between them. Ahead of them is the steep street of red beaten earth, seemingly dry but fertile, as can be seen from the patches of green grass stubbornly growing. The sculpture is not jarringly out of place in among these simple houses and this earth: even though its texture is different (it is made simply of wood and ce¬ment), the colours mix together and blend with their surround¬ings, and this is surely no accident. According to Caetano, the sculptures in this series Construção [Construction] (2005-2006) are almost houses: they are like small slums made to drift, like shacks, mocked up living spaces. They are sculptures with no place or destination. And the men understood perfectly: the idea being to push the sculpture up the hill in a Sisyphean effort with the aim of then letting it roll down the hill to the bottom. If along the way it comes up against an obstacle, and bounces, breaks and splits its tired skeleton made of demolition material against the front of one the houses and stops there, that is also fine: it has always been a sculpture without a place or destination any¬way... (though fortunately it does survive: it seems its awkward lopsided appearance makes it look more fragile than it really is).

In the most metaphysical chapter of the marvellously metaphysi¬cal masterpiece that is The Little Prince , the protagonist is a lamp-lighter who, alone on the smallest of all the planets, lights and puts out his lamp one thousand four hundred and forty times a day. The little prince would have liked to make friends with the lamp-lighter but his planet is really too small. There is no space for two. Caetano’s sculptures are also too small: each one can contain only one house, completely out of scale, proportionately huge, one immense undeniable idea of a house that takes up the entire planet, like the lamp on the lamp-lighter’s planet. When they are close to the others, in the metaphysical emptiness of the gallery’s white cube, they seem to aspire to make up a kind of constellation, each one a tiny roughly finished planet floating by. And it is true that they have no destination, nor fixed position: they seem to ask to be touched, lightly pushed at first to gauge their weight and the force needed, with the fear that they may break, and then more forcefully until they finally roll as if sud-denly awoken, and they move rocking forwards and backwards until they find a new position in which to stop, and go back to sleep until someone else decides to approach and push them again. And when one realises that it is through this movement, rolling violently or gently from one position to another, that they show their true forms, something moves inside them. Perhaps inside are sticks, or pebbles, or even chunks of mortar. It is hard to tell. But there is something there, and it hits the walls with the sound of waves beating the shore or perhaps like a heart that suddenly begins to race. In repose, the object is fascinating, even beautiful in its stubborn simple resistance, in its inelegance and charming appearance of a fallen fool, but it is clear that it only truly makes sense when spurred into action.

So perhaps the purpose of the sculpture, its reason for being, is precisely to make people gather round it, touch it, play with it, discuss the curious sensation of pushing an object around in an art gallery: its most conventional and traditionally sculptural elements (its almost abstract form, its weight, its earthy colours) serve in the end only to allow it access to the world of artistic production and fruition. Its real meaning, more profound and au- thentic, is in its ability to bring people together, inviting participa- tion, effort – whether personal or collective. Just as the sculpture cannot be considered conventional, neither can the effort that it invites, it does not have a practical result: it neither promises nor brings with it any concrete return. In other words, what we touch and what we do when faced with these planets of wood and ce- ment, are different from what we were thinking: something hard to sum up in words, and which has little to do with what we would expect of a sculpture.

In Caetano’s production, this apparent incongruity between the characteristics and formal references of a work and its true meaning is nothing new: for example in the works that use sugar as their primary material, the iconography is methodi- cally negated or challenged by the material itself. So, in Cristo de rapadura (2004) the apparent sacredness of the sculpture is exploded – literally, by the invitation to break off pieces of it to eat; in the series Brinquedos (2005), the sugar reproductions of dolls, cars, hobby horses and scooters exalt the sweetness of children’s games, just as the ephemeralism of the material becomes a yearning metaphor for its fleetingness, and just as the Cabec¸as [Heads](2007) of Brazilians , due to the inevitable impermanence of their material, take on the value of authentic mementi mori.

In other work sugar is used for architectural more than sculptural purpose: it creates corners and defines paths, through its simple presence it obliges one to rediscover the banality of the urban environment, suggesting through its transitory nature the possi- bility of having inadvertently, like Alice, gone through the looking glass. The first work/action of this series, Canto Doce (2004) was shown at the Bienal do Barro de Maracaibo in Venezuala, where the artist fixed a reproduction corner made of sugar over a real corner of the gallery; it looked like something organic, al¬most decomposing, but was offered to visitors as something to be tasted and eaten. The choice of a corner is not an idle one, as it starts a dialogue with works that were fundamental for the formation of an expanded field of sculpture in the second half of the twentieth century: for example, at the end of the 1960s Richard Serra created several sculptures, tautologically called Splashing and Casting, where he splashed molten lead in the corners of the walls and floor of his friend Jasper Johns’ stu¬dio. With its unfinished, almost edible appearance, these works mark Serra’s move away from his more conventionally minimal¬ist production. At the same time (1968-69) Cildo Meireles began his series Espaços virtuais: Cantos [Virtual spaces: Corners], which consisted of wooden sculptures that questioned euclid¬ean principles of space, and the intangible relationship between the outer corner of a building and its internal equivalent. In both cases, the aim was to start from a closed domestic space, and to explode it (whether physically as in the violent action of Serra’s Splashing, or mentally in the case of Cildo Meireles). However, Caetano appears to take a different path: the concept of edible architecture transports us to a dream world, closer to the fairy¬tales of the Brothers Grimm than to the anthropophagical world which the Brazilian context would imply. His Casa de Cupim [Termites’ House] (2005), a little termite house balanced on a small wooden stool, confirms this reading, as it persists with the strange, typically oneiric incongruity of scale: the planet of wood and cement has been transformed into a stool, but the house itself is still immense to its inhabitants who, either unconsciously or because of their excessive passion for it, consume it.

Recent works, in which sugar takes on clear and precise forms (like the walls that block pathways and impede circulation), ex¬emplify the relational intent behind the artist’s architectonic in¬terventions, his interest in what happens between the created space and the person moving within it, and in the interpersonal relations that the modification of the space encourages and fa¬vours. For example, the walls of unrefined sugar raised as part of the group of work entitled Algo bom [Something good](2005), interfere in walkways, pavements, the hall of the Calçado train station in Salvador, and even in busy roads, thus creating a new route, in the artist’s own words. These interventions in Caetano’s career seems to confirm the relevance of his production in an in¬ternational context. Barriers, whether permanent or ephemeral, have been constructed on more than one occasion by artists such as Santiago Sierra, who hired the driver of an enormous truck to park it across one the main streets of Mexico City, thus blocking the traffic for several minutes; Narda Alvarado, who achieved a similar result by making a troop of Bolivian police line-up in the centre of a street in La Paz in order for each one to eat an olive; or the Chinese artist Lin Yilin, who crossed the Lin He Road in Guangszhou, building and taking down a wall of grey bricks under the perplexed gazes of the builders working on the countless building sites surrounding the street itself.

Perhaps the most pertinent reference is Richard Serra, whose work Tilted Arc, was cut down and removed from the Federal Plaza in New York on the night of March 15 1985, four years af¬ter it had been installed, bringing what had been an enormously polemical process to an end. The work, an iron wall of almost 4 metres high and 40 metres long, had bisected the square, oblig¬ing pedestrians, and especially the employees of the surround-ing buildings, to take a detour around it. The epilogue, in the case of Caetano’s works, could be analogous: the labyrinth in the Calçada train station is for example, bitten, eaten, pieces of it torn away, until virtually nothing is left apart from the struts that supported it. In other places, one can imagine, the scene would have been more or less similar, but it is not the final result that is important here, rather it is how it was achieved. Here again, what is important for the artist is the process, the way in which people approach the work, touch it, test it, exchange glances and im-pressions, the attention it catalyses and how this is heightened by the bewilderment provoked by the material: yet again, the object seems, despite its evident unquestionable materiality, to be there only through its ability to bring people together.

Jacopo Crivelli

Jacopo Crivelli Visconti is a freelance curator and writer. Among other exhibitions, he has curated the Brazilian participation in the 52nd Venice Biennial in 2007.

Caetano Dias’ last solo exhibition in Bahia was in 2002, but since then he has continued to broaden his participation in the art world, aware as he is of the importance of discovering other cultures, of sharing experiences and of maintaining a dialogue between artists as well as art students. He has had exhibitions and has been artist in residence in São Paulo, Rio de Janei¬ro, Africa, Spain and France. His latest exhibition at the Paulo Darzé Galeria de Arte will offer a broader and more up-to-date view of his production and thinking. His work treats the sphere of human themes and politics, and the latter is fundamental to his work. Transverso is the body, memory, time and space; they are presented from a critical perspective (but no less delicate for this) and they reveal themselves in silent protest, themes transform themselves, double up, show themselves constantly super-imposed on one another, and in this movement they trans¬late the artist’s concerns and his desire to transform the world. Politics and poetry, effect and perception, reason and emotion: this dialectic game touches us, making us aware of the power of the work, and it transforms us, leading us to active, conscious, reflective and engaged participation. When I look at some of these works I hear a whisper. At some times a sigh; at others the sound of breathing. It could even be an echo of groans separat¬ing themselves from the failed promise that they are the images of architecture in ruins, mute portraits of past memories, stories contained between themselves. “It is strange, but ruins always have something natural about them” 1. We look at these images (which challenge me: decipher me, and devour me), and more than the immediate and most obvious reference to time and its passing, to memory and forgetfulness – all of which are recurring themes in his work – we are confronted in this series of photo¬graphs with the absence of man, whose presence is evidenced thus, becoming omnipresent.

This missing presence – or present absence – shows itself throughout the photographs in this exhibition. In the submerged path (or is it here a shipwreck?), in the remains of the skeleton of an old dwelling, in the resistance of solitary paths or destroyed buildings. Or of tattered old homeless furniture from wastelands, pieces of land that have witnessed the uncertainty and instability of an extreme and belittling social condition. Of the photos of old water tanks from the underwater town of Remanso from the series Água Invertida [Inverted Water], almost surreal in their condition as subverted objects, denouncers of a world turned on its head. In any case, there are only visible remains, which tell one of a pre-human landscape, and at the same time recount their journey and the necessity of fate: the landscape which man aspires to become. And then, when I am contemplating the ruins of a building, I notice the sky. I notice that the lines of the under¬water landscape in the water lead me upwards to the sky; that another path, one invaded and suffocated by vegetation guides me to the horizon. And that a shadowy, obscure landscape points to an almost floating stairway: it does no matter where it leads to, it offers us multiple possibilities.

There is the surprising existence of the skeleton (more than a structure) of a building site by the sea, placed on the border be¬tween the safety of the earth and the instability of the unknown sea. Just like the young Socrates’ dream, in which he finds a strange object by the sea that he is unable to classify, we too are confronted with an ambiguous disconcerting situation. In his dream, Socrates is confused by the enigma of the found object – is it a product of nature? An artefact made by a craftsman? Unable to answer, he throws it in the sea in the belief that this will calm him. Of course, this does not happen: further questions arise from the earlier one, and Socrates becomes a philosopher.

Time is confused, the elements are mixed up. Unstable ground. An earth being, a look backwards, material that blends the fu¬ture.

But also, and above all, a look forwards, upwards, to what is to come. Just like Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in What is Philosophy?, liberating fate, world fate, universal fate, through contemplation.

Fate is a strong presence in the ideas of other works by Caetano Dias, and particularly so in the video O mundo de Janiele. In this, a teenage girl, on the top of a building in the middle of a slum, indefinitely spins a hula-hoop. Despite the adverse time and space, and despite being a symbol of an oppressive situa¬tion, Janiele keeps up the movement, which, delicate, is almost like the engine of the world. The music, a ritornello, calming and comforting, emphasises the indefinite movement. Innocence as a weapon, and a markedly political attitude, in the sense that love for the world enables us to make the choice –according to Hannah Arendt – to push away the ruins of the world, to preserve the oasis (of art, love, philosophy, friendship) that can stop it being ravaged.

Two recent works – the video Fazendo Água and the video doc¬umentary 1978 – Cidade Submersa – are based on a true event in the interior of Bahia: the town of Remanso was flooded in 1978 to make way for the Sobradinho dam, and Nova Remanso was built to house the inhabitants of the old town. In addition to the reality of the situation, the idea and image of a town disap¬pearing under the water are also powerful ones, and bring to mind a phrase from Jorge Luis Borges’ book The Aleph which sums up the absurdity: “We easily accept reality, perhaps be¬cause we sense that nothing is real”. Caetano Dias reiterates this inversion of roles, this topsy-turvy world, but he offers us a poetical way out, aware that art transforms and is an alternative to the ruins of the world.

Stella Carrozzo

Salvador, Bahia, março de 2010

Cf. Marc Augé, Le temps en ruines, Éditions Galilée, 2003

Stella Carrozzo nasceu em Erchie, Itália, 1966. Artista visual formada pela Escola de Belas Artes da UFBA e gestora cultural. Utiliza-se em seu trabalho de múltiplas expressões, desde o desenho e a gravura à fotografia e vídeo. Faz parte do grupo ‘A Roda’, de Teatro de Bonecos, desde sua formação, em 1997. Atualmente, é Assessora Artística do Museu de Arte Moderna da Bahia - MAM-BA.